Hey, friend! Welcome back to another post. Today, I want to show you some of the historic markers I found around the town of Norman, Oklahoma. This list is different from the list of historic markers that are at the University of Oklahoma (OU). To see a list of markers at OU please see this blog post, “Historic Markers at the University of Oklahoma (OU).”

*The markers have been transcribed below each picture set. I will continue updating this post as I find more historic markers in Norman!

The Beginning of Cleveland County

“Although the Norman on-site was settled during the Land Run on April 22, 1889, Cleveland County did not exist for another year, and almost wasn’t named Cleveland County. In fact, if not for the efforts of Norman’s early citizens and civic leaders, Norman, Noble, Lexington, and Moore would now be part of Oklahoma County.

In 1890, the Fifty-First Congress of the United States began to draft the bill which would provide for a government in the newly settle Unassigned Lands. Early on, the location of county seats was limited to six towns: Oklahoma City, Guthrie, El Reno, Kingfisher, Stillwater, and Beaver (in No Man’s Land).

The presence of a district court and courthouse was an asset to any town, and Norman Mayor D.W. Marquart and others began to lobby Congress to add a seventh county seat at Norman. Mayor Marquart sent several telegrams petitioning the House Committee in Washington; one telegram requested the county seat due to “Norman being centrally located and a town of importance commercially as well as in size and number of inhabitants.”

The efforts were successful, and on Ma 2, 1890, President Benjamin Harrison signed the Oklahoma Organic Act, which created the Oklahoma Territory and established Norman as one of the the county seats. George W. Steele was nominated by President Harrison to be the first Governor of the Oklahoma Territory and his first official act on May 24, 1890 involved setting boundaries for the new counties. The future Cleveland County was referred to only as the “Third County.”

The original north boundary of the Third County was located at what is now 59th Street in Oklahoma City; it was moved to 89th Street in 1891. The original east boundary was the Pottawatomic Indian Treaty line, located near present-day 132nd Ave. SE in Norman; it was later moved six & one-half miles east.

Governor Steele called for an election, to be held on August 5, 1890, to choose a permanent name for the Third County. The editor of the Norman Transcript suggested “Little River County”, but local political parties had other plans. The Democrats held caucuses on July 26 and chose the name “Mansur County” in honor of Charles Mansur (U.S. Representative, Missouri, 1887-1893) because he had supported the settlement of the Unassigned Lands. Two days later, county Republicans announced their choice of “Lincoln County”, in honor of slain President Abraham Lincoln. After hearing the Republican choice, Democrat party leaders called an emergency session to choose a new name. William C. Renfrow, a prominent Norman businessman, suggested “Cleveland County”, after former President Grover Cleveland.

When the election was held on August 5, the Democrats won by a wide margin: “Cleveland County” received 829 votes while “Lincoln County” received 405. (Renfrow’s role in the win was duly noted by Democrats, and when Grover Cleveland was elected to a second term as U.S. President in 1893, he removed then-Governor Abraham Seay, a Republican, from office and appointed Renfrow in his place).”

*Historic marker is located on the lawn of the Cleveland County Courthouse.

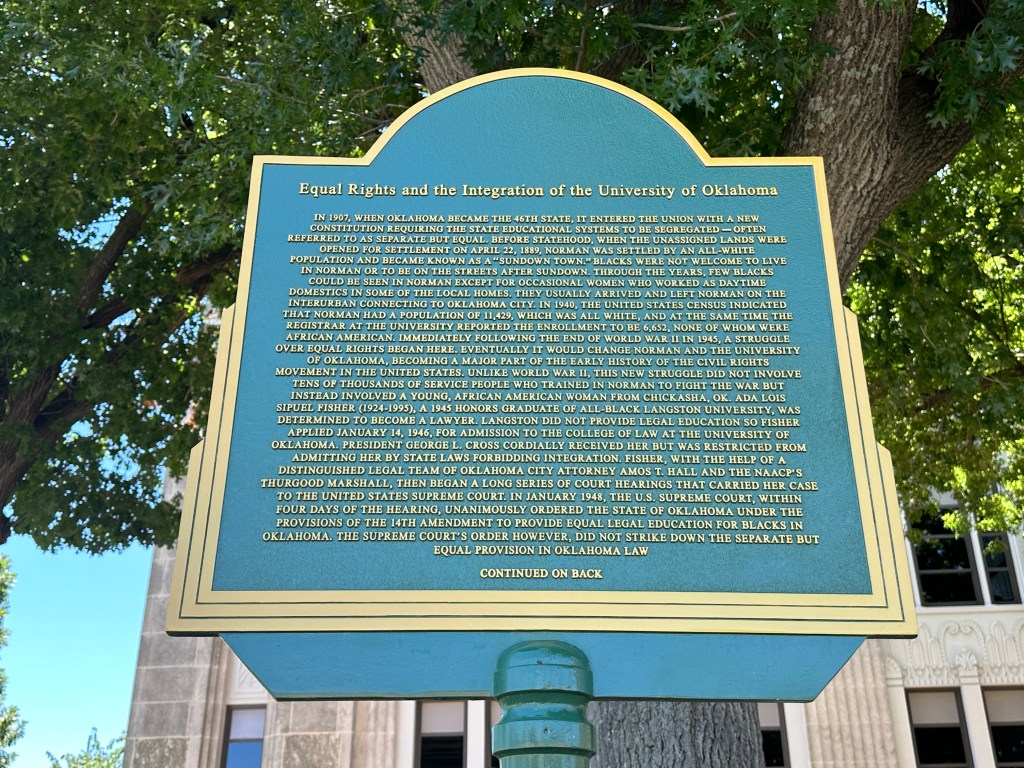

Equal Rights and the Integration of the University of Oklahoma

“In 1907, when Oklahoma became the 46th state, it entered the Union with a new constitution requiring the state educational systems to be segregated – often referred to as separate but equal. Before statehood, when the Unassigned Lands were opened for settlement on April 22, 1889, Norman was settled by an all-White population and became known as a “Sundown Town.” Blacks were not welcome to live in Norman or to be on the streets after sundown. Through the years, few Blacks could be seen in Norman except for occasional women who worked as daytime domestics in some of the local homes. They usually arrived and left Norman on the interurban connecting to Oklahoma City. In 1940, the United States Census indicated that Norman had a population of 11,429, which was all White, and at the same time the Registrar at the University reported the enrollment to be 6,652, none of whom were African American. Immediately following the end of World War II in 1945, a struggle over equal rights began here. Eventually it would change Norman and the University of Oklahoma, becoming a major part of the early history of the Civil Rights Movement in the United States. Unlike World War II, this new struggle did not involve tens of thousands of service people who trained in Norman to fight the war but instead involved a young, African American women from Chickasha, OK. Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher (1924-1995), a 1945 Honors Graduate of All-Black Langston University, was determined to become a lawyer. Langston did not provide legal education so Fisher applied January 14, 1946, for admission to the College of Law at the University of Oklahoma. President George L. Cross cordially received her but was restricted from admitting her by state laws forbidding integration. Fisher, with the help of a distinguished legal team of Oklahoma City attorney Amos T. Hall and the NAACP’s Thurgood Marshall, then began a long series of court hearings that carried her case to the United States Supreme Court. In January 1948, the U.S. Supreme Court, within four days of the hearing, unanimously ordered the state of Oklahoma under the provisions of the 14th Amendment to provide equal legal education for Blacks in Oklahoma. The Supreme Court’s order however, did not strike down the separate but equal provision in Oklahoma law.

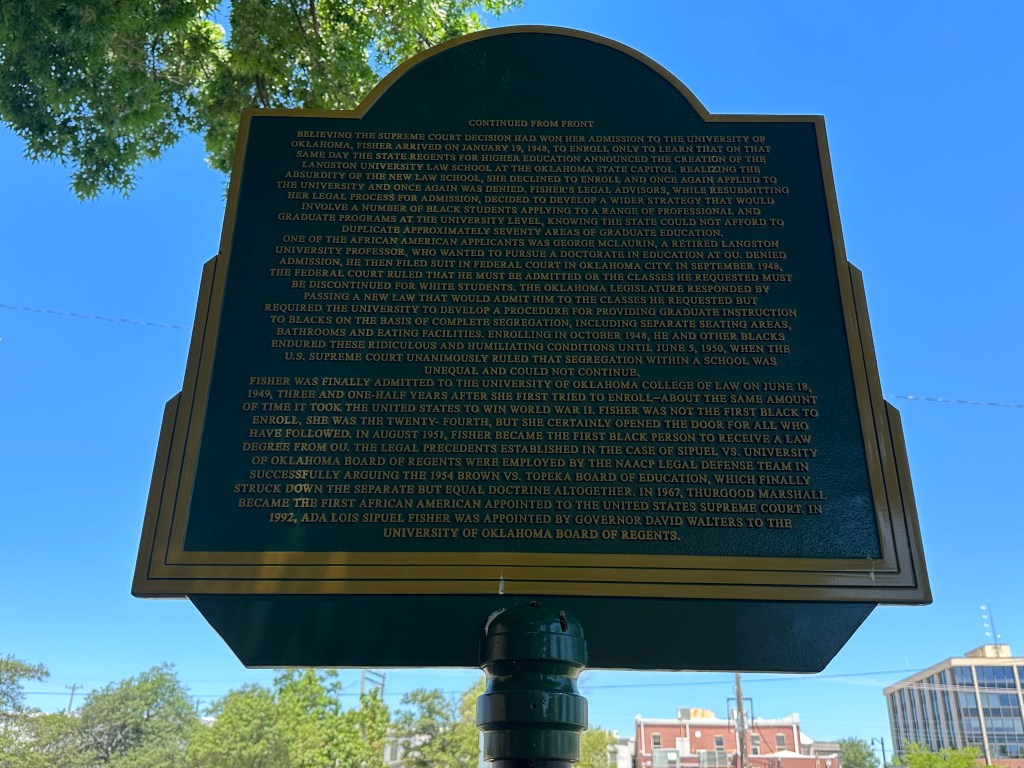

Believing the Supreme Court decision had won her admission to the University of Oklahoma, Fisher arrived on January 19, 1948, to enroll only to learn that same day the State Regents for Higher Education announced the creation of the Langston University Law School at the Oklahoma State Capitol. Realizing the absurdity of the new law school, she declined to enroll and once again applied to the University and once again was denied. Fisher’s legal advisors, while resubmitting her legal process for admission, decided to develop a wider strategy that would involve a number of Black students applying to a range of Professional and Graduate programs at the university level, knowing the state could not afford to duplicate approximately seventy areas of graduate education.

One of the African American applicants was George McLaurin, a retired Langston University professor, who wanted to pursue a doctorate in education at OU. Denied admission, he then filed suit in Federal Court in Oklahoma City. In September 1948, the Federal Court ruled that he must be admitted or the classes he requested must be discontinued for White students. The Oklahoma Legislature responded by passing a new law that would admit him to the classes he requested but required the University to develop a procedure for providing graduate instruction to Blacks on the basis of complete segregation, including separate seating areas, bathrooms and eating facilities. Enrolling in October 1948, he and other Blacks endured these ridiculous and humiliating conditions until June 5, 1950, when the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously ruled that segregation within a school was unequal and could not continue.

Fisher was finally admitted to the University of Oklahoma College of Law on June 18, 1949, three and one-half years after she first tried to enroll – about the same amount of time it took the United States to win World War II. Fisher was not the first Black to enroll, she was the twenty-fourth, but she certainly opened the door for all who have followed. In August 1951, Fisher became the first Black person to receive a law degree from OU. The legal precedents established in the case of Sipuel vs. University of Oklahoma Board of Regents were employed by the NAACP legal defense team in successfully arguing the 1954 Brown vs. Topeka Board of Education, which finally struck down the separate but equal doctrine altogether. In 1967, Thurgood Marshall became the first African American appointed by Governor David Walters to the University of Oklahoma Board of Regents.”

*Historic marker is located on the lawn of the Cleveland County Courthouse.

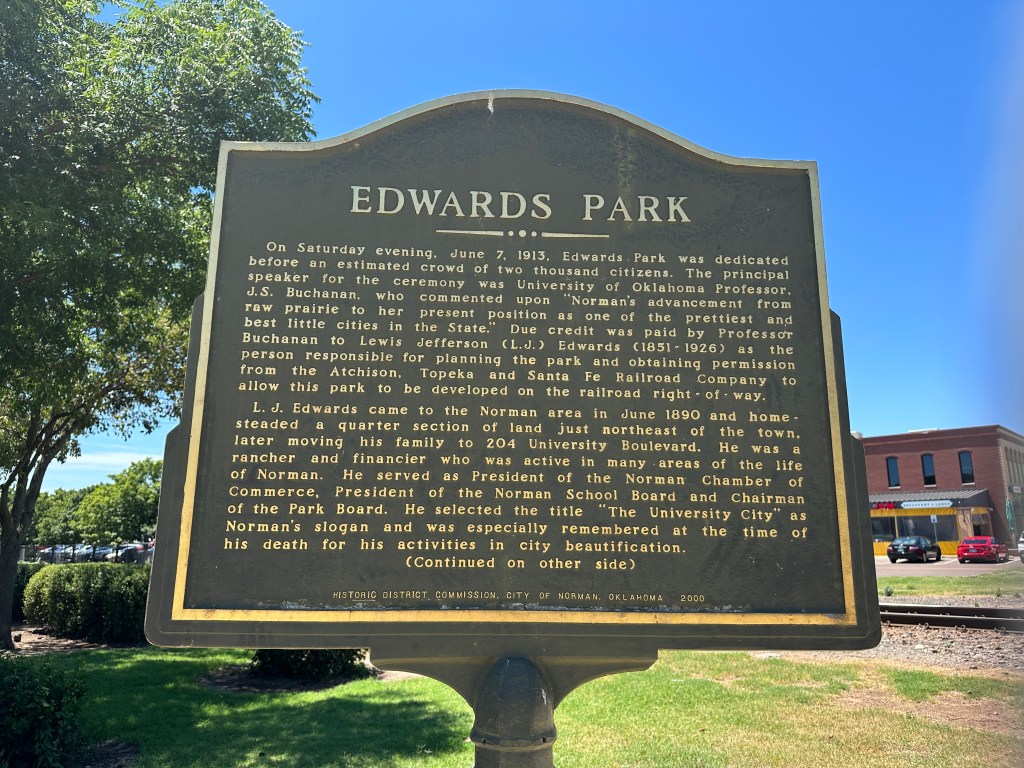

Edwards Park

“On Saturday evening, June 7, 1913, Edwards Park was dedicated before an estimated crowd of two thousand citizens. The principal speaker for the ceremony was University of Oklahoma Professor, J.S. Buchanan, who commented upon “Norman’s advancement from raw prairie to her present position as one of the prettiest and best little cities in the State.” Due credit was paid by Professor Buchanan to Lewis Jefferson (L.J.) Edwards (1851-1926) as the person responsible for planning the park and obtaining permission from the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Company to allow this park to be developed on the railroad right-of-way.

L.J. Edwards came to the Norman area in June 1890 and homesteaded a quarter section of land just northeast of the town, later moving his family to 204 University Boulevard. He was a rancher and financier who was active in many areas of the life of Norman. He served as President of the Norman Chamber of Commerce, President of the Norman School Board and Chairman of the Park Board. He selected the title “The University City” as Norman’s slogan and was especially remembered at the time of his death for his activities in city beatification.

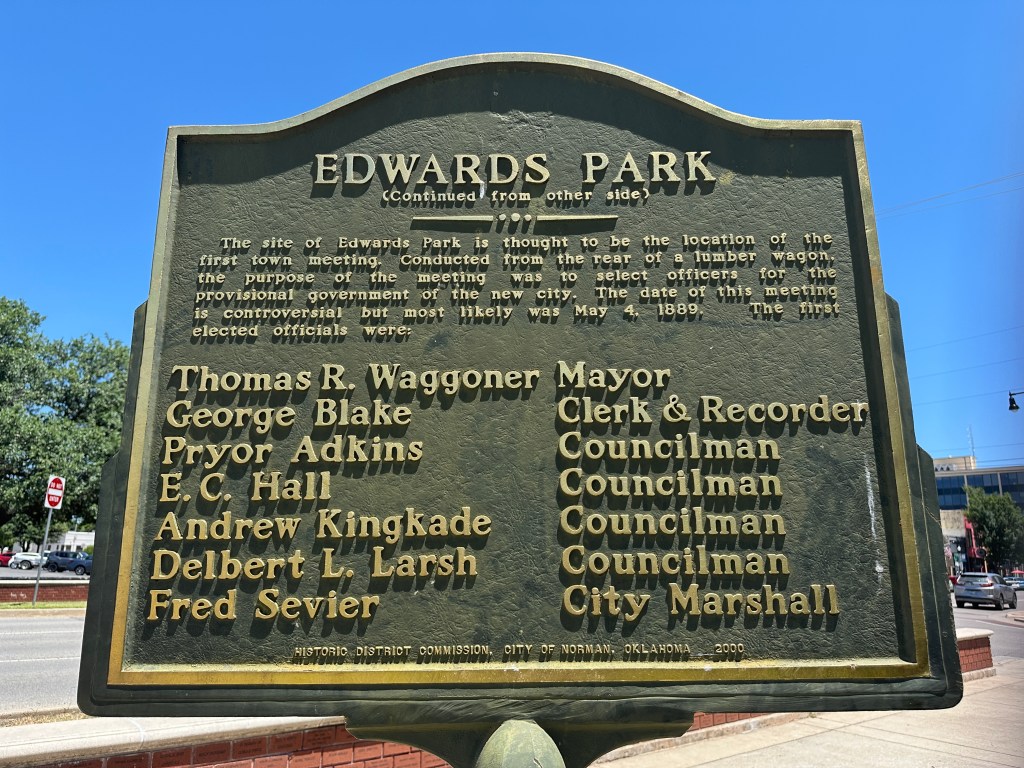

The site of Edwards Park is thought to be the location of the first town meeting. Conducted from the rear of a lumber wagon, the purpose of the meeting was to select officers for the provisional government of the new city. The date of this meeting is controversial but most likely was May 4, 1889. The first elected officials were:

Thomas R. Waggoner (Mayor), George Blake (Clerk & Recorder), Pryor Adkins (Councilman), E.C. Hall (Councilman), Andrew Kingkade (Councilman), Delbert L. Larsh (Councilman), Fred Sevier (City Marshall)

*Historic Marker is located near the James Garner Statue on the Legacy Trail.

The Jacobson House

“The home of Swedish born artist, Oscar B. Jacobson & Jeanne d’Ucel became a center for international celebrities, artists & writers, 1918-1966. Jacobson, Director, of O.U. School of Arts, 1915-45, revolutionized art education in Oklahoma. He is also credited with nurturing the “renaissance” of Native American painting on the Southern Plains in the 1920s.”

Leave a comment