Hey, friend! Welcome back to another post. Today, I want to show you a handful of historic markers I was able to find within walking distance of the hotel I stayed at in Dallas. Let’s get started!

Formerly the Texas School Book Depository Building

“Formerly the Texas School Book Depository Building” Guillot operated a wagon shop here. In 1894 the land was purchased by Phil L. Mitchell, President and Director of the Rock Island Plow Company of Illinois. An office building for the firm’s Texas Division, known as the Southern Rock Island Plow Company, was completed here four years later. In 1901 the five-story structure was destroyed by fire. That same year, under supervision of the company vice president and general manager F.B. Jones, work was completed on this structure. Built to resemble the earlier edifice, it features characteristics of the commercial Romanesque Revival Style.

In 1937 the Carraway Byrd Corporation purchased the property. Later, under the direction of D.H. Byrd, the building was leased to a variety of businesses, including the Texas School Book Depository.

On November 22, 1963, the building gained national notoriety when Lee Harvey Oswald allegedly shot and killed President John F. Kennedy from a sixth floor window as the Presidential Motorcade passed the site.”

*This marker is on the outside of the Sixth Floor Museum building.

The Old Red Courthouse

“Designated as public land in John Neely Bryan’s 1844 city plat, this was the site of a log courthouse built after Dallas County was created in 1846. When Dallas won election as permanent county seat in 1850, Bryan deeded the property to the county, and a larger log structure was erected. In 1856 county offices occupied a 2-story brick edifice, rebuilt in 1860 after a fire that almost destroyed the city. The fourth courthouse, a 2-story granite structure erected in 1871, survived one fire in 1880 before it burned again in 1890.

The old red courthouse, the fifth seat of county government, was begun in 1890 and completed in 1892. Designed by architect M.A. Orlopp, it exemplifies the Romanesque revival style with its massive scale and rounded arches. The blue granite of the lower floor and window trim contrasts with the red sandstone of the upper stories. Eight circular turrets dominate the design. A clock tower with a 4500-ound bell originally topped the building, but it was removed in 1919. Two of the four clay figures perched on the roof have also been removed.

To house the expanding county government, a new courthouse was built in 1965. Some offices remained in the 1890 structure, which was renovated in 1968.”

*This marker is on the outside of the Old Red Courthouse building on the East side of the building.

Log Cabin Pioneers of Dallas County

“Most colonists first settled in this “Three Forks” area of the Trinity River as members of the Peters Colony after 1841. Immigrants from such states as Arkansas, Illinois, Kentucky, Missouri, and Tennessee brought with them a tradition of building log shelters.

Land title was granted to the settlers who worked at least 15 acres and built “a good and comfortable cabin upon it.” This region was abundant in oak, juniper (popularly called cedar), walnut, ash, bois d’arc, and elm trees, which furnished sturdy building timbers.

John Neely Bryan, a colonist from Tennessee, arrived near this site in late 1841 and built a log cabin in 1842. The area’s first school and church was built of logs at Farmer’s Branch (12 Mi. NW) in 1845. J.W. Smith and J.M. Patterson brought goods from Shreveport (184 Mi. E) in 1846 for resale at their log store in Dallas.

Milled lumber appeared in Dallas buildings by 1849, and bricks were available by 1860. That year a fire destroyed most of the town’s original log cabins.

The nearby log cabin was built out of cedar logs before 1850, possibly by Kentuckian Guide Pemberton. It was moved from its original site (7.5 Mi. E) in 1926 and rebuilt at several locations, including Bryan’s designated courthouse site (1 Blk. SW) in 1936, and this block in 1971.”

*This marker is next to the John Neely Bryan Cabin across the street from the JFK Memorial. It is at angle across the street from the Old Red Courthouse.

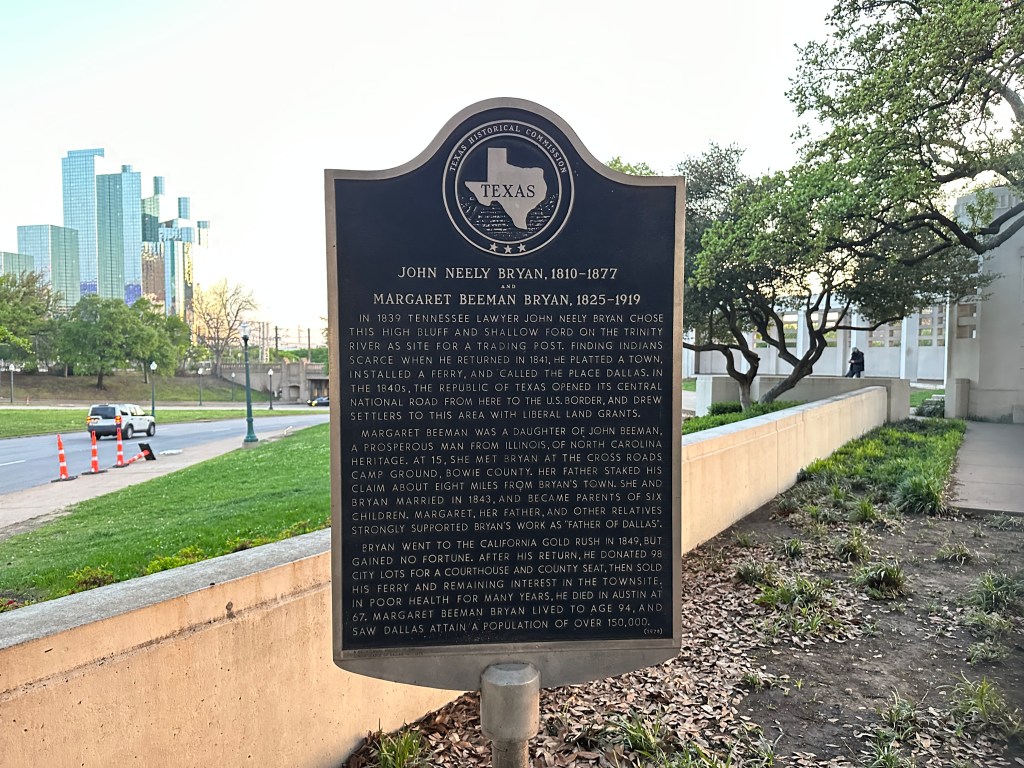

John Neely Bryan, 1810-1877 & Margaret Beeman Bryan, 1825-1919

“In 1839 Tennessee Lawyer John Neely Bryan chose this high bluff and shallow ford on the Trinity River as site for a trading post, finding Indians scarce when he returned in 1841, he platted a town, installed a ferry, and called the place Dallas. In the 1840s, the republic of Texas opened its central national road from here to the U.S. border, and drew settlers to this area with liberal land grants.

Margaret Beeman was a daughter of John Beeman, a prosperous man from Illinois, of North Carolina heritage. At 15, she met Bryan at the cross roads camp ground, Bowie County. Her father staked his claim about eight miles from Bryan’s town. She and Bryan married in 1843, and became parents of six children. Margaret, her father, and other relatives strongly supported Bryan’s work as “Father of Dallas”.

Bryan went to the California Gold Rush in 1849, but gained no fortune. After his return, he donated 98 city lots for a courthouse and county seat, then sold his ferry and remaining interest in the townsite. In poor health for many years, he died in Austin at 67. Margaret Beeman Bryan lived to age 94, and saw Dallas attain a population of over 150,000.”

*This marker is next to the WPA project on the Grassy Knoll in Dealey Plaza next to the Sixth Floor Museum.

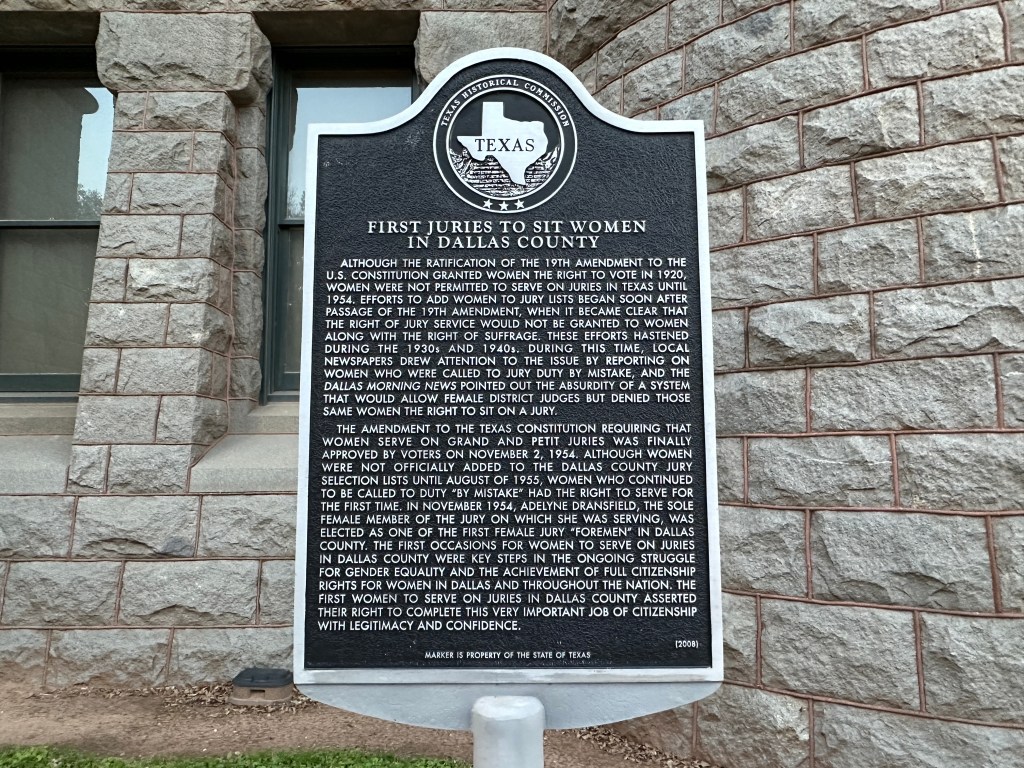

First Juries to Sit Women in Dallas County

“Although the ratification of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution granted women the right to vote in 1920, women were not permitted to serve on juries in Texas until 1954. Efforts to add women to jury lists began soon after passage of the 19th Amendment, when it became clear that the right of jury service would not be granted to women along with the right of suffrage. These efforts hastened during the 1930s and 1940s. During the time, local newspapers drew attention to the issue by reporting on women who were called to jury duty by mistake, and the Dallas Morning News pointed out the absurdity of a system that would allow female district judges but denied those same women the right to sit on a jury.

The Amendment to the Texas Constitution requiring that women serve on Grand and Petit juries was finally approved by voters on November 2, 1954. Although women were not officially added to the Dallas County jury selection lists until August of 1955, women who continued to be called to duty “by mistake” had the right to serve for the first time. In November 1954, Adelyne Dransfield, the sole female member of the jury on which she was serving, was elected as one of the first female jury “Foremen” in Dallas County. The first occasions for women to serve on juries in Dallas County were key steps in the ongoing struggle for gender equality and the achievement of full citizenship rights for women in Dallas and throughout the nation. The first women to serve on juries in Dallas County asserted their right to complete this very important job of citizenship with legitimacy and confidence.”

*This marker is next to the Old Red Courthouse building on the East side of the building.

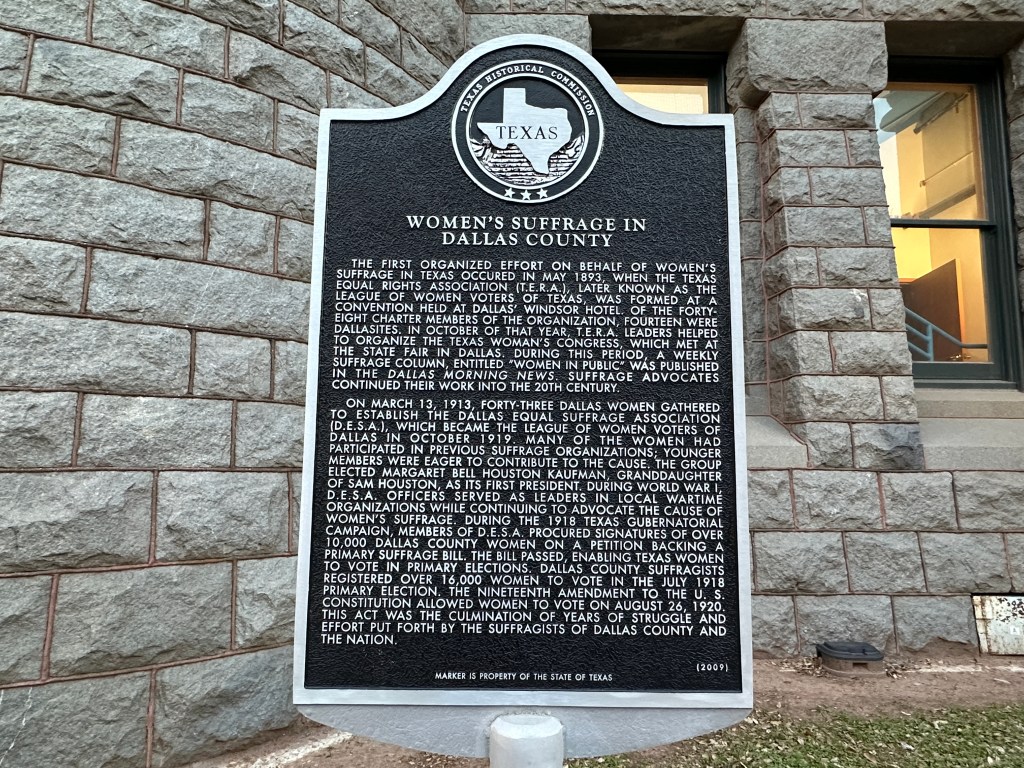

Women’s Suffrage in Dallas County

“The first organized effort on behalf of women’s suffrage in Texas occurred in May 1893, when the Texas Equal Rights Association (T.E.R.A.), later known as the League of Women Voters of Texas, was formed at as convention held at Dallas’ Windsor Hotel. Of the forty-eight charter members of the organization, fourteen were Dallasites. In October of that year, T.E.R.A. leaders helped to organize the Texas Woman’s Congress, which met at the State Fair in Dallas. During this period, a weekly suffrage column, entitled “Women in Public” was published in the Dallas Morning News. Suffrage advocated continued their work into the 20th century.

On March 13, 1913, forty-three Dallas women gathered to establish the Dallas Equal Suffrage Association (D.E.S.A.), which became the League of Women Voters of Dallas in October 1919. Many of the women had participated in previous suffrage organizations; younger members were eager to contribute to the cause. The group elected Margaret Bell Houston Kaufman , granddaughter of Sam Houston, as its first president. During World War I, D.E.S.A. officers served as leaders in local wartime organizations while continuing to advocate the cause of women’s suffrage. During the 1918 Texas Gubernatorial Campaign, members of D.E.S.A. procured signatures of over 10,000 Dallas County women on a petition backing a primary suffrage bill. The bill passed, enabling Texas women to vote in Primary elections. Dallas County suffragists registered over 16,000 women to vote in the July 1918 Primary election. The Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution allowed women to vote on August 26, 1920. This act was the culmination of years of struggle and effort put forth by the suffragists of Dallas County and the nation.”

*This marker is next to the Old Red Courthouse building on the East side of the building.

1910 Lynching of Allen Brooks

“After Reconstruction, White Southerners began adopting laws and codes, known as Jim Crow Laws or Black Codes, that affected everyday life for African Americans. One instrument of enforcement was the threat of violence as well as actual violence, including lynching. Although more often associated with rural areas, lynchings did occur in towns and cities. In Dallas County between 1853 and 1920, five White males and six African American males were lynched by mobs. The lynching of Allen Brooks on March 3, 1910, was an example of strategic Jim Crow violence.

As recorded in major newspapers, court records and personal testimonies, Allen Brooks was a 65-year-old African American laborer accused of assaulting a girl while working at the home of a regular employer. Local law enforcement attempted to keep the time and location of the pretrial hearings secret, but a local newspaper published the information and a mob subsequently convened at the county courthouse. Measures were taken to secure the building and pulled Brooks to the second-floor window. The mob placed a rope around his neck and threw him from the window. They then dragged Brooks half a mile down Main Street where he was finally hung from a telephone pole near the prominent Elks Arch at Main and Akard Streets. Following this horrific event, witnessed by an estimated 5,000 people, many citizens called for a state special Grand jury to investigate the lynching, but no court convened and no one was held accountable. Although no other lynchings were documented in the city of Dallas after 1910, other forms of racial discrimination and oppression persisted.”

*This marker is next to the Old Red Courthouse building on the Southwest corner of the building.

Alexander Cockrell & Sarah Horton Cockrell

Alexander Cockrell (June 8, 1820 – April 3, 1858)

Sarah Horton Cockrell (Jan. 13, 1819 – April 26, 1892)

“Alexander Cockrell came to Dallas area in 1845. After serving in the war with Mexico (1846-47), he filed on 640 acres in the Peters Colony, and married Sarah Horton on Sept. 9, 1847. Cockrell operated a freight line to Houston, Jefferson, and Shreveport until 1852, when he purchased remainder of the Dallas Townsite from John Neely Bryan (1810-77), the “Father of Dallas”.

Cockrell promoted growth of the village in the mid-1850s by building a brick factory, a sawmill, and a bridge across the Trinity River, replacing a ferry he had bought from Bryan. Cockrell’s influence on Dallas’ prosperity ended April l3, 1858, when he met an untimely death in an altercation over an unpaid debt.

Sarah Horton Cockrell became the first woman in Dallas to exert economic influence outside the home. She completed the unfinished St. Nicholas Hotel, and rebuilt it after the fire of July 8, 1860; operated the ferry after the bridge collapsed in 1858, until a new span was erected in 1872; and added a flour mill and other businesses to the community. The Cockrells’ enterprises played a vital role in the establishment of Dallas as an early regional trade center.”

*This marker was next to a WPA project with walking distance of the Old Red Courthouse. I’m sorry I didn’t grab the address.

Concluding Thoughts

I enjoyed finding these historic markers in historic district in downtown Dallas, Texas. I had scouted a couple of these markers on Google maps before my trip, but was pleasantly surprised to find more once I started walking around. I learned more about the history of Dallas and Texas that I didn’t know before.

I hope you’ll look for historic markers next time you’re driving around a big city!

Happy traveling, friend! I’ll talk to ya soon 🙂

Leave a comment